This all started because I love to ask people questions about their job.

In the summer of 2019, I met Mel who told me they were part of a team of people giving around-the-clock care to an elderly woman with dementia.

This elderly woman didn’t realize that the people who were stopping by every day to hang out were actually her caregivers. They were feeding her, getting her outside for a walk, and spending time with her.

Every day at 10am there was a shift change. The person who had already spent the night would say they were going to get the mail. Outside, they’d meet the new caregiver on the walkway and exchange notes. Then the new caregiver would go in with the mail and the elderly woman wouldn’t have noticed the switch.

The premise of this story hooked me. The idea that to care for someone in this situation, that it was necessary to lie1 to them— for their benefit— really moved me.

And then I learned that this woman was Phyllis Lyon, who I knew as a legendary San Francisco activist and lesbian icon.

I had first heard of Phyllis when I moved to San Francisco in 2004 and same-sex marriages were first declared legal by then-mayor Gavin Newsom. Phyllis and her partner Del Martin were recruited to be the first same-sex couple to be legally wed, an honor they earned after a lifetime of trailblazing activism and organizing on behalf of the gay and lesbian community.

It was not surprising that Phyllis’ caregivers were queer and trans people, dedicating a day or more of their work week to keep a beloved queer elder safe and healthy. Outside of their time with Phyllis, they had careers as gardeners, performers, filmmakers, and writers. It was a unique role: a demanding job that required grit and the always-on alertness of a caregiver, coupled with the chance to participate in a lineage of care for an elder who had paved the way for them and others.

I reached out to Kendra Mon, Del Martin’s biological daughter, who, along with family friend and accountant Pan Haskins, helped create a unique caregiving model for Phyllis.

In September of 2019, I started interviews with caregivers, including Kendra and Pan, and gathered my last bits of tape just before lockdown in early March of 2020.

As part of my research, I searched the audio archives of the GLBT Historical Society and the Lesbian Herstory Archives. I am also grateful for the permission to use audio from this episode of Making Gay History and a short clip from Peter L Stein’s Hidden Neighborhoods series for PBS, “The Castro.”2

The audio piece and article below, was first published on KALW in June of 2020, a few months after Phyllis passed on April 9, 2020, five years ago today.3

Caring for an Icon, with Love and Deceit

Intro

Dottie Lux is a nightlife performer in burlesque and drag shows around the city. But it's arguably her day job that's more interesting. She's a caregiver for queer elder and activist Phyllis Lyon. In the winter of 2019, Dottie is pulling up in front of Phyllis' house for her shift.

"She's well into her nineties," Dottie says. "She still cannot conceive of needing help, from washing her dishes to washing her butt. And to convince her that she does need help is not possible," Dottie says lovingly.

At the foot of the stairs to Phyllis's house, Dottie points to the initials "PL + DM" carved into the sidewalk. She convinced a construction worker to let her draw Phyllis and her partner Del Martin's initials into the wet cement a few months ago.

"She's famous!" Dottie told him.

The construction worker, she imagined, wouldn't know why.

LGBTQ Trail Blazer

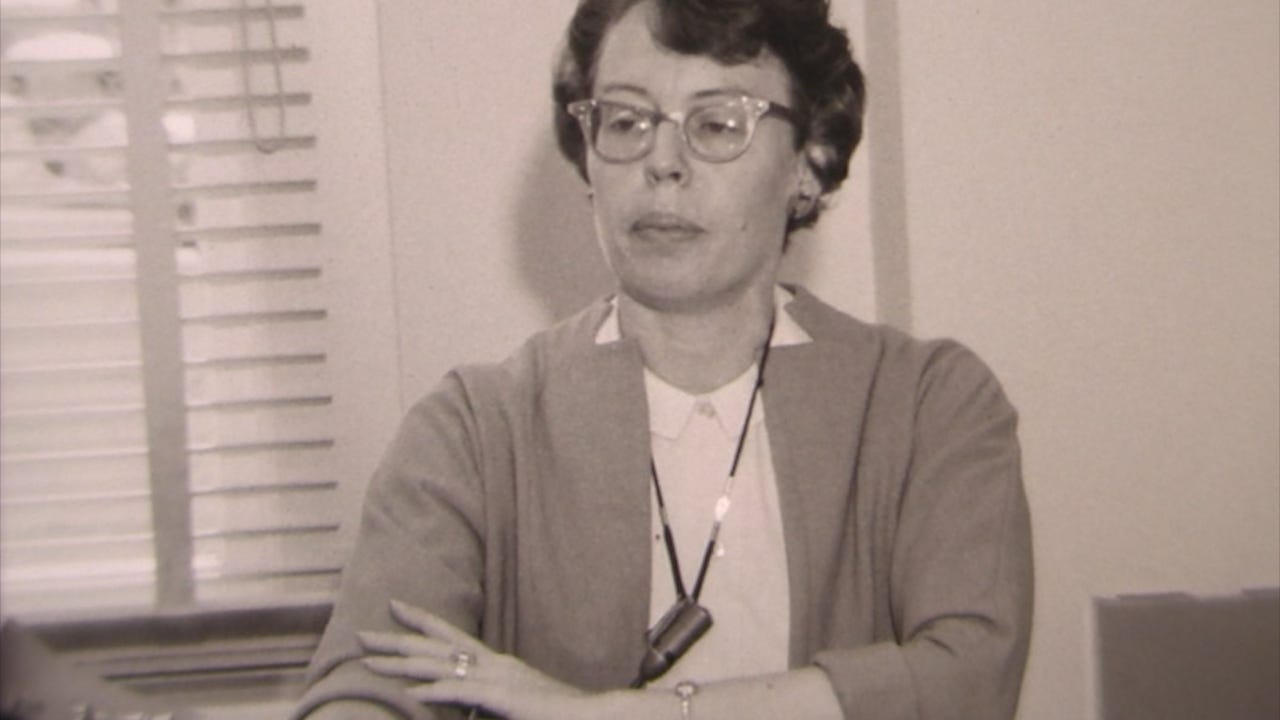

Phyllis Lyon was born in Tulsa, Oklahoma in 1924. Her family moved to Sacramento when she was in high school. She studied journalism at Berkeley and covered the police beat in Fresno. When she moved to Seattle to write for a trade journal, one of her co-workers was a woman named Del Martin. Del was a lesbian and she wasn't shy about it— an anomoly at the time. Phyllis was fascinated by Del, and for a year they were just friends.

Until one day, the story goes, Del made a “half a pass, and Phyllis completed it.”

In 1953, Phyllis and Del bought a small house on Clipper Street in the Noe Valley. One of the best features of the home was a huge living room window with a near view of the San Francisco skyline.

Phyllis and Del knew very few lesbian couples in San Francisco, so they were excited when a friend wanted help starting a social group for lesbians. They formed Daughters of Bilitis, or DOB, to be a gathering where women could dance and meet each other while staying safe. They met at Phyllis and Del’s home and would draw the front curtains to conceal their dancing from people on the street. But its focus quickly shifted towards politics and eventually DOB, became the first national lesbian organization. They distributed their newsletter, The Ladder, across the country and Phyllis was the editor.

The Ladder published information about the gay community and experience that you couldn't find anywhere else at the time. Homosexuality was criminalized in the fifties and people kept their true sexuality a secret. If they were found out, it could cost them their jobs or their family and friends.

In 1965, Phyllis helped create another group that brought together religious leaders with queer activists to advocate for gays and lesbians. Four years before Stonewall, they organized a fundraiser costume ball. Drag queens and clergymen showed up. So did the cops. Heterosexual religious leaders got to witness first-hand how gay people were being targeted by the police. Phyllis and Del also helped to create a hotline to report police intimidation, harassment, and violence.

In 1972, Phyllis and Del wrote the pathbreaking book 'Lesbian/Woman', which described and affirmed the lesbian experience.

"There'd been loads and loads of books about male homosexuals," Phyllis said, "and there hadn't been anything on lesbians that was worth talking about."

They continued to be politically active in their later years. Congresswoman Nancy Pelosi appointed Phyllis and Del to the White House Conference on Aging in 1995.

Phyllis and Del didn't care much about marriage, but they also felt that denying gays and lesbians the right to marry relegated them to second class citizens. When California legalized gay marriage, Phyllis and Del were invited to be the first couple married and became the face of gay marriage in San Francisco. Their wedding was officiated by Mayor Gavin Newsom. But two months after they legally married and 55 years since they got together, Del Martin passed away.

And that's when things began to change.

Secret Caregivers

There are many friends and family who are part of the story that comes next. One of them is 71-year old Pan Haskins, who had been Phyllis and Del's bookkeeper for decades.

After Del died, "We were all very concerned for Phyllis." Pan and other friends organized a network to support Phyllis, who had begun struggling with everyday tasks. Pan says Phyllis had learned how to manage so that some of her friends didn't realize she was showing signs of dementia.

But by 2013, it was clear Phyllis needed help. Strangers would call when she was home alone and Phyllis would try and write them checks. Phyllis let the insurance on the house lapse. Phyllis left the stove on and nearly started a fire. And when her daughter, Kendra Mon, tried to talk to her about these things, they would argue.

"There's no sense in arguing with somebody who has memory loss," Kendra said. "It quickly became clear that we just needed to take care of things without her knowledge. I got good at lying."

Kendra and Pan met with experts on dementia at UCSF who gave them guidance. One of the things they emphasized was that little lies are okay if it helps Phyllis accept help and care.

Kendra and Pan hatched a plan that would 'trick' the fiercely independent Phyllis into receiving the care she needed. They told Phyllis a young lesbian who was interested in lesbian history wanted to come over. This young lesbian was actually a caregiver Kendra and Pan had hired, named Carrie Schell. The premise was realistic.

"A lot of young lesbians are really impressed by Phyllis Lyon and want to hang out with her," Carrie says.

At first, Carrie would come by for just a few hours a day. She pretended she was helping Phyllis archive her newspaper clippings.

"It wasn't very long before she kind of forgot where I came from and how long I'd been around," Carrie said. "So in that way, her memory loss kind of worked in the favor of her getting care."

Daughter Kendra understood that if Phyllis knew that Carrie was a paid caregiver, Phyllis would feel diminished. So they let her believe she was living independently.

"By disrespecting her and lying, we're respecting her," Kendra said. "We're keeping her image of herself, the way she wants it to be."

Still, Phyllis was in charge. Carrie would come by the house to see if Phyllis was in the mood to hang out. Sometimes they'd have lunch at Phyllis's favorite spot in Noe Valley, the now-shuttered Savor restaurant.

But one day when Phyllis was alone, she fell and hurt herself. Kendra and Pan decided she needed 24-hour care. Would they be able to find and train other people like Carrie? They tried the most obvious thing first: hiring caregivers from an agency. But this didn't work. Caregivers would show up in scrubs with a pillow and Phyllis would turn them away.

"The minute somebody would say, I'm a caregiver, she would say, ‘Get the hell out of my house,’" Carrie said.

Now the goal was to find the kind of people who could get in the door and pass the 'Phyllis test.' And part of passing that test meant being queer. Carrie said that hiring queer and trans people was a crucial part of caring for Phyllis because queer people share cultural references. They speak the same cultural language. One day Carrie showed up at Phyllis's after getting out of work and referred to her own outfit as her “office drag.”

"She doesn't know what day it is. She doesn't know what happened five minutes ago, but she still knows what “office drag” is," Carrie said.

Carrie was able to find other queer and trans caregivers through friends and referrals. She found people that revered Phyllis like a queer grandma and that loved listening to her stories about the early days of Daughters of Bilitis.

It was important they didn't mind if Phyllis was a little flirty.

"When I'm trying to get her to do something, I flirt back, you know?" Dottie said.

Phyllis was known to be playful with caregivers, especially if you were femme-presenting like Dottie. Caregivers said Phyllis was more attentive on the days they dressed up and looked cute for their shift.

"We'd be driving in the car," said caregiver Celeste Chan. "And I'd make a comment about how hot it was and she'd be like, you're a hot kid."

Caregivers would bring Phyllis out to a park or the beach. They'd hang out in queer spaces like drag brunch where she could enjoy the attention that comes with being a 'gaymous' activist.

"She loves being recognized," Celeste said. "She loves when people see her on the street and they're like, 'Oh, I know who you are. Thank you for all that you've done.'"

Best Laid Plans

In November of 2019, Phyllis' caregivers gathered for their quarterly meeting in Phyllis’ living room. It’s Phyllis' ninety fifth birthday and some old friends have taken her out to lunch to celebrate.

At the meeting, the group discusses her end of life planning. Unless Phyllis is in physical pain, they are instructed not to call 911. The group agrees: it is to Phyllis's benefit to be able to “ease out of life,” rather than have it prolonged at any cost just to live longer.

The house isn't just a meeting place for the caregivers; it's actually the reason why Phyllis can get this kind of care in the first place. The house she bought in 1953 for eleven thousand dollars, situated on hill a double lot with a view.

Kendra, Pan and close friends cobbled together a unique financial set up to pay for Phyllis's 24-hour care. And it all hinges on the value of Phyllis's home.

Basically, wealthy friends— mostly older lesbians— donated funds that pay the caregivers. And, Kendra explains, when Phyllis passes and after the house is sold, that money will go back to the original investors.

"Phyllis is so lucky, and doesn't have any clue," Kendra says.

It's a gift that Phyllis can live in her own home, Kendra says.

"She has friends who ask her about stories from her past and remind her of all the great things she's accomplished."

"In a just and equitable world, we could hold and care for every elder the way we hold and care for Phyllis," Pan says.

Carrie adds that to get this level of care, you have to be wealthy or an icon like Phyllis.

"I would love to see a queer community that takes care of elders in the same way that people take care of her" Carrie says.

Death Of An Icon

By March 2020, less than a week before San Francisco's shelter-in-place orders, Phyllis's health was deteriorating. She had to have an eye on her at all times after a recent fall. A month later on April 9, Phyllis Lyon passed away.

The thoughtfulness that went into her caregiving also went into planning for her death, but COVID-19 got in the way. Family and friends gathered over Zoom for a funeral. Her community of caregivers still miss her in their lives.

"Everything that Phyllis did in her life was revolutionary and without fear," Dottie said, "I think that fearlessness is her biggest legacy."

"Care doesn't have to look so clinical, it can instead look like friendship," Celeste said. "It can be a true exchange between people."

Carrie echoed this feeling.

"We don't need institutions. We can do this with just each other."

Phyllis and Del were the grandmothers of the lesbian movement, Pan said.

"It will be great to say we showed up and were able to do the work we did and provide her that dignity at the end of her life."

All of their lives, Phyllis and Del were trying to create community. Kendra says in their later years, they expressed some hurt and disappointment that younger lesbians thought their thinking was outdated and that they were no longer relevant. But Kendra thinks that the younger generation of caregivers is the continuation of the community that Del and Phyllis created, albeit a community that Phyllis might not have realized she helped create.

Since Phyllis's death, the caregivers have continued her legacy and created their own club, the Granddaughters of Bilitis.

Postscript:

After Phyllis passed, her home went on the market and was sold for 2.25 million. I assume that the original donors that made Phyllis’ care situation possible were then reimbursed their original investment.

There was a moment when it seemed like the house was going to be bought and preserved as a historical landmark, but the funds could not be raised.

Sadly, Pan Haskins passed away in October of 2021.

More Info about Phyllis and Del:

Lyon & Martin Community Health Services, named after Phyllis and Del. Lyon-Martin provides high quality, compassionate medical and mental health care services targeting trans, non-binary, gender non-conforming, and intersex (TGI) communities and cis-gender women.

No Secret Anymore: The Times of Del Martin and Phyllis Lyon (Trailer): Documentary about Phyllis and Del’s public work and private relationship. Available on Vimeo, Kanopy, Alexander Street, Amazon Prime

Lesbian/Woman by Del Martin/Phyllis Lyon, considered to be a foundational work of lesbian feminism.

Margie Adam in conversation with Phyllis Lyon at StoryCorps in 2010 (I wish I knew this tape existed when I made this piece!)

When You Look Out the Window, a picture book that points out the San Francisco landmarks they could see from their living room window.

Phyllis and Del as grand marshalls of the Freedom Day Parade, 1989

Footage of the marriage in 2004, care of the California Musuem

HBO’s docuseries “Equal” featured actresses portraying Phyllis and Del.

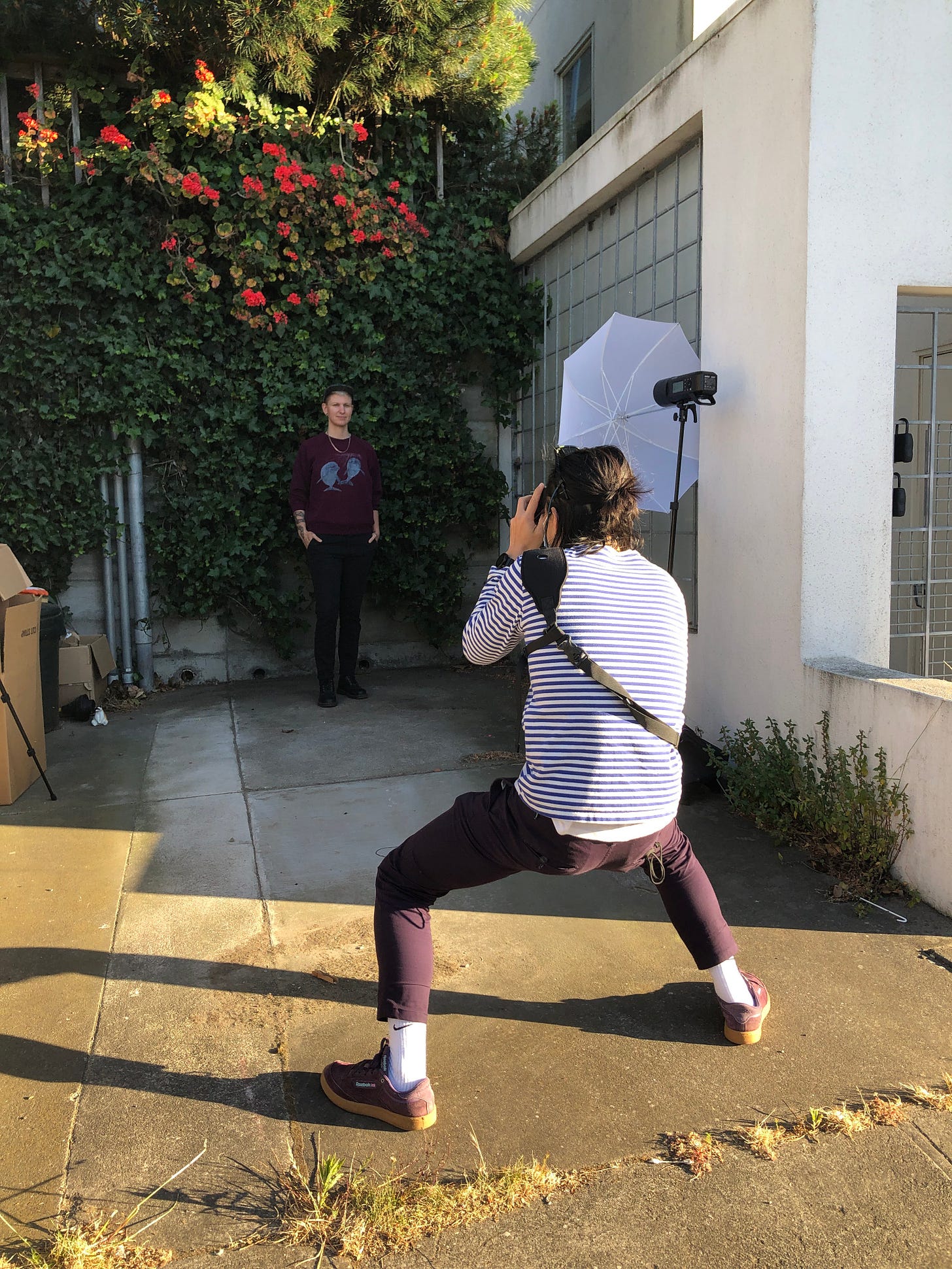

Thank you to YunFei Ren for his photography!

I later learned this a method employed when dealing with someone who has dementia. You can tell small lies that will help them accept their situation and to accept help and care.

“The Castro” is not online, but here’s an interview with Stein and Teri Gross on “Fresh Air” in 1998 about its production.

Thank you to my fantastic editor, Marissa Ortega-Welch!